Moving from Ruby to Rust

How we migrated our Tier 1 service from ruby to rust and didn’t break production.

Table of Contents

- Background

- Why Rust?

- How we made Ruby talk to Rust

- Moving from Ruby to Rust

- Performance Improvements

- Conclusion

Background

In the Logistics Algorithms team, we have a service, called Dispatcher, the main purpose of which is to offer an order to the rider, optimally. For each rider we build a timeline, where we predict where riders will be at a certain point of time; knowing this, we can more efficiently suggest a rider for an order.

Building each timeline involves a fair bit of computation: using different machine learning models to predict how long events will take, asserting certain constraints, calculating assignment cost. The computations themselves are quick, but the problem is that we need to do a lot of them: for each order, we need to go over all available riders to determine which assignment would be the best.

The first version of the Dispatcher was written mainly in Ruby: this was a go-to language in the company, and it was performing adequately given our size at the time. However, as Deliveroo kept growing, the number of orders and riders increaed dramatically, and we saw that the dispatch process started taking much longer than before and we realised, that at some point it will be impossible to dispatch some areas within a time constraint that we put in place. We also knew that is was limiting us if we decided to implement more advanced algorithms, which would require even more computation time.

The first thing we tried was to optimise the current code (cache some computations, try to find a bug in the algorithms), which didn’t help much. It was clear that Ruby was a bottleneck here and we started looking at the alternatives.

Why Rust?

We considered a few approaches to how to solve the problem of dispatch speed:

- choose a new programming language with better performance characteristics and rewrite the Dispatcher

- identify biggest bottlenecks, rewrite those parts of the code and somehow integrate them in the current code

We knew that rewriting something from scratch is risky, as it can introduce bugs, and switching services over can be painful, so we didn’t feel quite comfortable with this approach. Another option, finding bottlenecks and replacing them, was something that we did already for one part of the code (we built a native extension gem for the Hungarian route matching algorithm, implemented in Rust), and that worked well. We decided to try this approach.

There were several options how we could integrate parts of the code written in another language to work with Ruby:

- build an external service and provide an API to communicate with

- build a native extension

We quickly discarded an option to build an external service, because either we would need to call this external service hundreds of thousands of times per dispatch cycle and the overhead of the communication would offset all of the potential speed gains, or we would need to reimplement a big part of the dispatcher inside this service, which is almost the same as a complete rewrite.

We decided that it has to be some sort of native extension, and for that, we decided to use Rust, as it ticked most of the boxes for us:

- it has high performance (comparable to C)

- it is memory safe

- it can be used to build dynamic libraries, which can be loaded into Ruby (using

extern "C"interface)

Some of our team members had experience with Rust and liked the language, also one part of the Dispatcher was already using Rust. Our strategy was to replace the current ruby implementation gradually, by replacing parts of the algorithm one by one. It was possible because we could implement separate methods and classes in Rust and call them from Ruby without a big overhead of cross-language interaction.

How we made Ruby talk to Rust

There a few different ways you can call Rust from Ruby:

- write a dynamic library in Rust with

extern "C"interface and call it using FFI. - write a dynamic library, but use the Ruby API to register methods, so that you can call them from Ruby directly, just like any other Ruby code.

The first approach, using FFI would require us to come up with some custom C like interfaces in both Rust and Ruby and then create wrappers for them in both languages. The second approach, using Ruby API, sounded more promising, as there were already libraries to make our lives easier:

We tried Helix first:

- it has macros which look like writing Ruby in Rust, which was a bit more magical for us than we were comfortable with

- the Coercion Protocol wasn’t well documented and it wasn’t clear how would you go about passing non-primitive Ruby objects into Helix methods

- we were not sure about the safety - it looked like Helix didn’t call Ruby methods using

rb_protect, which could lead to undefined behavior

Eventually, we decided to go with ruru/rutie, but keep the Ruby layer thin and isolated so that we could possibly switch in the future. We decided to use Rutie, a recent fork of Ruru which has more active development.

Here’s a small example of how you can create a class with one method in ruru/rutie:

#[macro_use]

extern crate rutie;

use rutie::{Class, Object, RString};

class!(HelloWorld);

methods!(

HelloWorld,

_itself,

fn hello(name: RString) -> RString {

RString::new(format!("Hello {}", name.unwrap().to_string()))

}

);

#[allow(non_snake_case)]

#[no_mangle]

pub extern "C" fn Init_ruby_rust_demo() {

let mut class = Class::new("RubyRustDemo", None);

class.define(|itself| itself.def_self("hello", hello) );

}

It’s great if all you need is to pass some basic types (like String, Fixnum, Boolean, etc.) to your methods, but not that great if you need to pass a lot of data. In that case, you can pass the whole object, say Order and then you would need to call each field you need on that object to move it into Rust:

pub struct RustUser {

name: String,

address: Address,

}

pub struct Address {

pub country: String,

pub city: String,

}

class!(User);

impl VerifiedObject for User {

fn is_correct_type<T: Object>(object: &T) -> bool {

object.send("class").send("name").try_convert_to::<RString>().to_string() == "User"

}

fn error_message() -> &'static str {

"Not a valid request"

}

}

methods!(

// .. some code skipped

fn hello(user: AnyObject) -> Boolean {

let name = user.send("name").try_convert_to::<RString>().unwrap().to_string();

let ruby_address = user.send("address");

let country = ruby_address.send("country").try_convert_to::<RString>().unwrap().to_string();

let city = ruby_address.send("city").try_convert_to::<RString>().unwrap().to_string();

let address = Address {

country,

city

};

let rust_user = RustUser {

name,

address

};

do_something_with_user(&rust_user);

Boolean::new(true)

}

)

You can see a lot of routine and repetitive code here, proper error handling is missing as well.

After looking at this code, it reminded us that this looks a lot like some manual parsing of something like JSON or similar.

You could instead serialize objects in Ruby to JSON and then parse it in Rust, and it works mostly OK, but you still need to implement JSON serializers in Ruby.

Then we were curious, what if we implement serde deserializer for AnyObject itself: it will take ruties’s AnyObject and go over each field defined in the type and call the corresponding method on that ruby object to get it’s value. It worked!

Here’s the same method, but using our serde deserializer & serializer:

#[derive(Debug, Deserialize)]

pub struct User {

pub name: String,

pub address: Address,

}

#[derive(Debug, Deserialize)]

pub struct Address {

pub country: String,

pub city: String

}

class!(HelloWorld);

rutie_serde_methods!(

HelloWorld,

_itself,

ruby_class!(Exception),

// Notice that the argument has our defined type `User`, and the return type is plain bool

fn hello_user(user: User) -> bool {

do_something_with_user(&user);

true

}

);

You can see how much simpler the code in hello_user is now - we don’t need to parse user manually anymore.

Since it’s serde, it can also handle nested objects (as you can see with the address).

We also added a built-in error handling: if serde fails to “parse” the object, this macro will raise an exception of a class that we provided (Exception in this case), it also wraps the method body in the panic::catch_unwind, and re-raises panics as exceptions in Ruby.

Using rutie-serde we could quickly and painlessly implement thin interfaces between ruby and rust.

Moving from Ruby to Rust

We came up with a plan to gradually replace all parts of the Ruby Dispatcher with Rust. We started by replacing with Rust classes which didn’t have dependencies on other parts of the Dispatcher and adding feature flags, something similar to this:

module TravelTime

def self.get(from_location, to_location, options)

# in the real world the feature flag would be more granular and enable you to do an incremental roll-out

if rust_enabled? && Feature.enabled?(:rust_travel_time)

RustTravelTime.get(from_location, to_location, options)

else

RubyTravelTime.get(from_location, to_location, options)

end

end

end

There was also a master switch (in this case rust_enabled?), which allowed us to switch all the Rust code off by flipping just one feature flag.

Since the API of both Ruby and Rust classes implementations remained largely the same, we were able to test both of them using the same tests, which gave us more confidence in the quality of the implementation.

RSpec.describe TravelTime do

shared_examples "travel_time" do

let(:from_location) { build(:location) }

let(:to_location) { build(:location) }

let(:options) { build(:travel_time_options) }

it 'returns correct travel time' do

expect(TravelTime.get(from_location, to_location, options)).to eq(123.45)

end

end

context "ruby implementation" do

before do

Feature.disable!(:rust_travel_time)

end

include "travel_time"

end

context "rust implementation" do

before do

Feature.enable!(:rust_travel_time)

end

include "travel_time"

end

end

It was also very important that, at any time, we could switch off the Rust integration and the Dispatcher would still work (because we kept the Ruby implementation along with Rust and kept adding feature flags).

Performance Improvements

When moving more larger chunks of code into Rust, we noticed increased performance improvements which we were carefully monitoring. When moving smaller modules to Rust, we didn’t expect much improvement: in fact, some code became slower because it was being called in tight loops, and there was a small overhead to calling Rust code from the Ruby application.

Performance numbers

In the Dispatcher, there are 3 main phases of the dispatch cycle:

- loading data

- running computation, calculating assignments

- saving/sending assignments

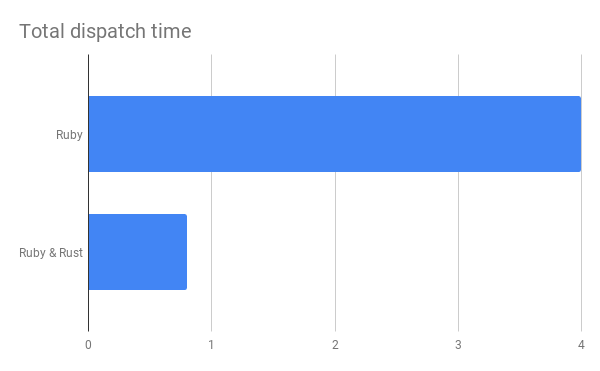

Loading data and saving data phases scale pretty much linearly depending on the dataset size, while the computation phase (which we moved to Rust) has an higher-order polynomial component in it. We are less worried about the loading/saving data phases, and we didn’t prioritise speeding up those phases yet. While loading data and sending data back were still parts of the Dispatcher written in Ruby, the total dispatch time was significantly reduced: for example, in one of our larger zones it dropped from ~4 sec to 0.8 sec.

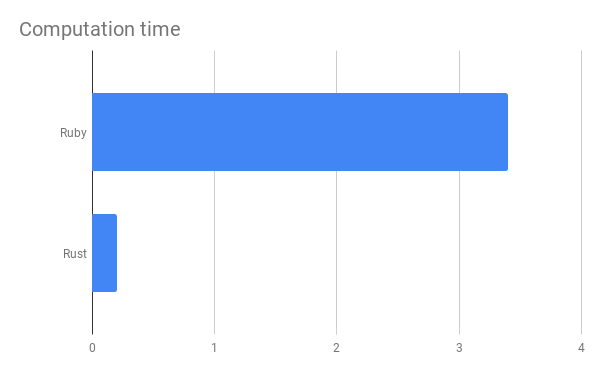

Out of those 0.8 seconds, roughly 0.2 seconds were spent in Rust, in the computation phase. This means 0.6 second is a Ruby/DB overhead of loading data and sending assignments to riders. It looks like the dispatch cycle is only 5 times quicker now, but actually, the computation phase in this example time was reduced from ~3.4sec to 0.2sec, which is a 17x speedup.

Keep in mind, that Rust code is almost a 1:1 copy of the Ruby code in terms of the implementation, and we didn’t add any additional optimisations (like caching, avoiding copying memory in some cases), so there is still room for improvement.

Conclusion

Our project was successful: moving from Ruby to Rust was a success that dramatically sped up our dipatch process, and gave us more head-room in which we could try implementing more advanced algorithms.

The gradual migration and careful feature flagging mitigated most of the risks of the project. We were able to deliver it in smaller, incremental parts, just like any other feature that we normally build in Deliveroo.

Rust has shown a great performance and the absence of runtime made it easy to use it as a replacement of C in building Ruby native extensions.